Practical Money: Do this NOW before selling any stock!

This one tip can save you lots of money on taxes

Introduction

The end of the year is fast approaching, which means two things: holiday stress is peaking, and a select few savvy investors (who actually remember how their brokerage account is set up) are using tax-loss harvesting to stick it to The Man. The rest of you? Well, you’re probably about to hand over a gratuitous gift to the IRS because of a single, criminally boring, easily-changed setting. Spoiler alert: it’s labeled “disposal method,” and it’s not referring to kitchen trash.

In this issue, I’ll discuss various disposal methods—not the kind that require gloves and a shovel, but the ones that can make or break your capital gains taxes. I’ll even reveal my personal choice, which, spoiler, is not selling my life’s savings at a loss just for fun.

Disclaimer: This is NOT financial advice. I am just sharing my strategies, investments, stocks, and index fund strategies, what I'm buying, and where I plan to take those investments. Everyone’s financial goals are different. No financial decisions should be made solely on this newsletter, which is for informational and entertainment purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for advice from a professional financial advisor or qualified expert.

Also, if you found this newsletter helpful, please share it with one friend who might find it useful by using the button below.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Quickly Explained

I took a deep dive into tax-loss harvesting a couple of years ago, including a bunch of examples, which you can read here. But in case you only have time for a tweet-sized summary: sell investments that have lost value, realize a capital loss, and use it to offset other gains. If you’re extra unlucky and losses exceed gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 against ordinary income, carrying the rest forward like an eternal party favor for future tax years. It’s like trading a sad stock for a big tax deduction.

The key is to remember the wash-sale rule, which prevents you from repurchasing the same or “substantially identical” investment within 30 days before or after the sale, or the loss won’t count. The IRS frowns on the “sell for a loss, buy right back immediately” strategy. They’re like that strict aunt who notices everything.

Capital Gains and Cost Basis

Dealing with investments and taxes can feel like navigating a maze designed by a bored CPA, except with higher stakes and more IRS forms. Understanding terms like Capital Gains, Cost Basis, and methods of disposal like First-In, First-Out (FIFO) is crucial for accurately reporting your income and minimizing your tax bill.

Capital Gains and Losses

A Capital Gain is the profit you realize when you sell a capital asset (like a stock, bond, or mutual fund share) for more than its cost basis. A Capital Loss is the opposite, a painful reminder of your poor judgment. In 2025, there are two main types of capital gains:

Short-term capital gains: For assets held one year or less. Taxed as ordinary income (10% to 37% for 2025) based on your federal tax bracket, because apparently making money too fast is frowned upon.

Long-term capital gains: For assets held longer than one year. Subject to lower, preferential tax rates (0%, 15%, or 20%), depending on taxable income. The government appreciates the stability, apparently.

Cost Basis

Cost basis is how much you paid for something, plus fees—think of it as the “I broke even, right?” number. Keeping a correct cost basis helps make sure you’re not tipping the IRS more than necessary. The formula (brace yourself for the math):

Capital Gain/Loss = Sale Price − Cost Basis

Why it’s crucial: An accurate cost basis ensures you only pay tax on the actual profit, not on the entire sale price. If you reinvest dividends, for example, your cost basis increases, which reduces your taxable gain when you eventually sell. Your brokerage firm reports this information to you and the IRS on Form 1099-B.

Disposal Methods

This is where the easy money is—or, rather, the easy money saving. This single choice can swing your tax bill from “Ouch” to “Hey, not bad.”

As an example, let’s assume that I own 400 shares of META that’s currently trading at $600 / share, and I plan to sell 100 shares. Let’s say I bought those shares over the years at these various prices (this is just an example; META never hit $900 in 2024):

2012: 100 shares at $5

2022: 100 shares at $200

2024: 100 shares at $900

2025: 100 shares at $800

Let’s also assume I’m living that glamorous top tax bracket life (20% long-term, 37% short-term). Now I’m selling 100 shares at $600 each. There are a bunch of disposal methods (Fidelity has 11). Here are the most popular and how they affect taxes.

FIFO (First-In, First-Out): The Default Disaster (Possibly)

This is the default method used by the IRS and many brokerage firms, loved by people who never change presets. The earliest shares purchased are sold first. This can result in higher capital gains (and higher taxes) if the oldest shares have appreciated the most.

So, for the META example using FIFO, since the shares bought at $5 were my oldest shares, FIFO requires those to be sold first, resulting in a very large gain. My cost basis using FIFO = 100 shares × $5 = $500.Now I’m selling those 100 shares at $600/share.

My sale proceeds = 100 × $600 = $60,000.

My capital gain is the sale proceeds - cost basis = $60,000 - $500 = $59,500.

Since my long-term capital gains tax rate is 20%, I would owe $11,900 in taxes (At a 20% long-term capital gains tax rate: $59,500 × 0.20 = $11,900). Congratulations! I turned a $500 investment into a five-figure tax bill. The government thanks me for my service and my portfolio cries a little.LIFO (Last-In, First-Out):

The most recently acquired shares are sold first. This may result in lower gains if recent purchases were at higher prices, but can also produce more short-term gains taxed at higher rates. Great for maximizing losses... if your most recent purchases were terrible.

So in this case, I would be selling 100 shares from the 2025 lot (which I bought at $800 / share).

My cost basis = 100 shares × $800 = $80,000.Now I sell those 100 shares at $600/share.

My sale proceeds = 100 × $600 = $60,000.

My capital gain (actually a loss) is the sale proceeds - cost basis = $60,000 - $80,000 = -$20,000.

Since it’s a loss, the tax rate is irrelevant—I pay $0 in capital gains tax and can use the $20,000 loss to offset gains (or up to $3,000 against ordinary income). If I use the $3,000 loss against ordinary income, I can carry the remaining $17,000 forward indefinitely.Tax Sensitive (Fidelity) / Tax Lot Optimizer (Charles Schwab)

This is the one I utilize, because I, too, enjoy not giving away more money than necessary. Most brokerages have some version of this. At Fidelity, it’s called “Tax Sensitive”, while at Charles Schwab, it’s called “Tax Lot Optimizer.” It sells shares that minimize your tax burden—usually the ones with losses first.

In this case, I would be selling the 2024 shares purchased at $900/share (the highest-cost shares). This produces the largest possible capital loss, which is the best outcome from a tax-optimization standpoint.

My cost basis = 100 shares × $900 = $90,000.Now I sell those 100 shares at $600/share.

My sale proceeds = 100 × $600 = $60,000.

My capital gain (actually a loss) is the sale proceeds - cost basis = $60,000 - $90,000 = -$30,000.

I would owe $0 in taxes, and the $30,000 loss can offset gains elsewhere. If unused, I can deduct $3,000/year against ordinary income and carry the remaining $17,000 indefinitely.

So for tax implications, this is the best option. Here, the $900 cost basis generates a bigger loss than the $800 shares. By not selling the 2012 and 2022 shares, I retain shares with massive unrealized gains. These can be used strategically later, like selling in a low-income year at a lower tax rate, donating for a full fair-market-value deduction, etc.

A Pretty Sweet Tax Trick

In the example provided, I sold 100 shares of META. In each example, I would end up left with 300 shares. But depending on the disposal method, I could have gone from owing $11,900 in taxes to taking a $30,000 loss. Not bad for a few dropdown clicks in my brokerage account.

One more thing I could do. In 30 days (to dodge the dreaded wash sale rule), I can buy 100 shares of META back. If we assume that the stock stays around $600, I am right back to where I started with 400 shares of META, but I now have a massive $30,000 capital loss on my tax returns.

The moral of the story is that you can have your cake, eat it, and then convince the IRS that the crumbs were an expense.

How To Check Your Disposal Method

If you don’t know what setting your account is on, you’re almost certainly using FIFO, which is akin to leaving your house keys under the welcome mat for the IRS. Seriously, go check. Every brokerage hides this setting differently, like an Easter egg only tax nerds care to find, but searching “Disposal Method” on your brokerage website should get you there. Here’s how to do it for Fidelity and Charles Schwab:

Fidelity

Select your account and go to “Account Features”. There, you should see an option for managing Cost Basis Information Tracking:

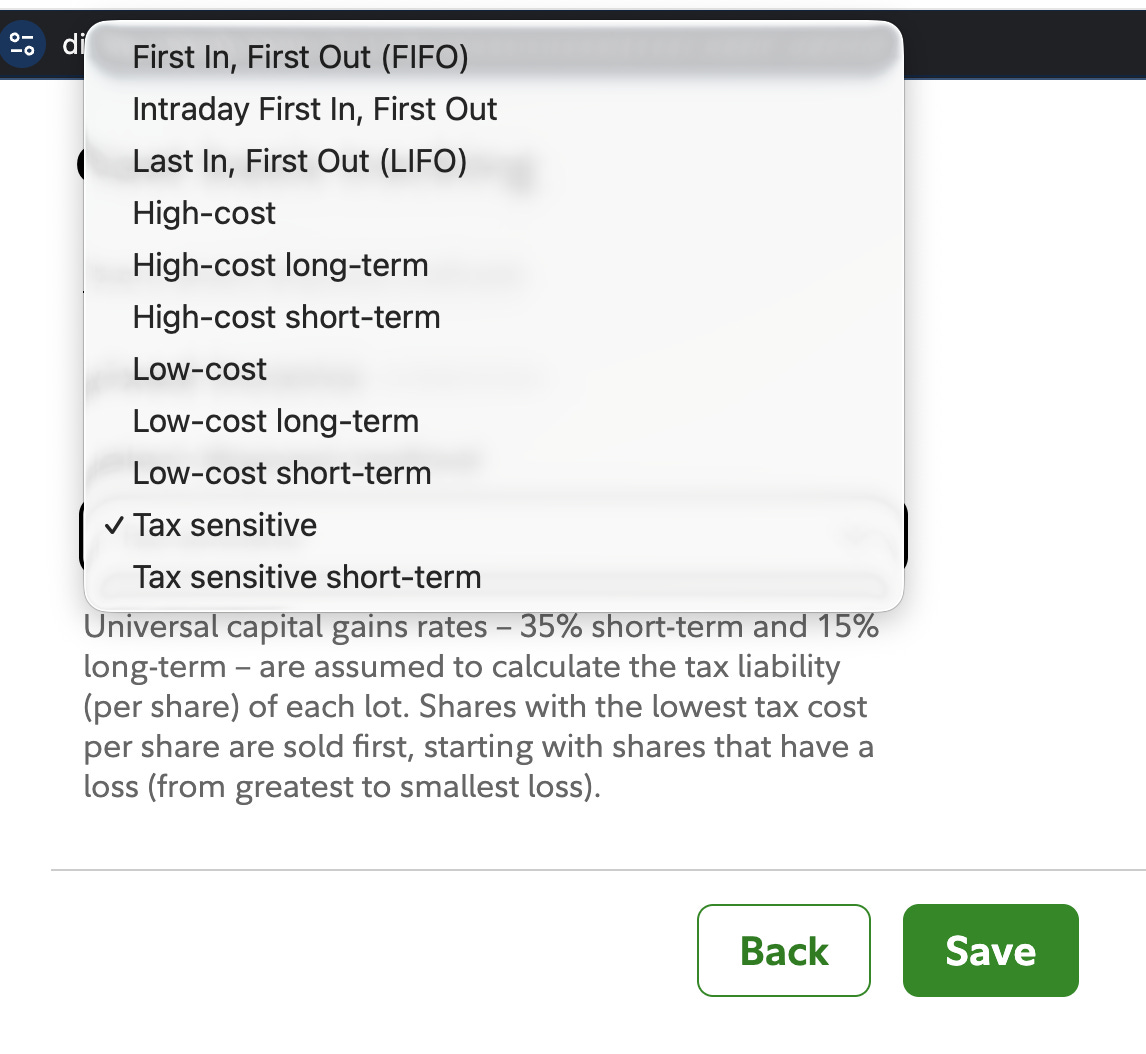

Once you click on “Manage”, you will see the disposal method selected as well as the other ones offered:

Charles Schwab

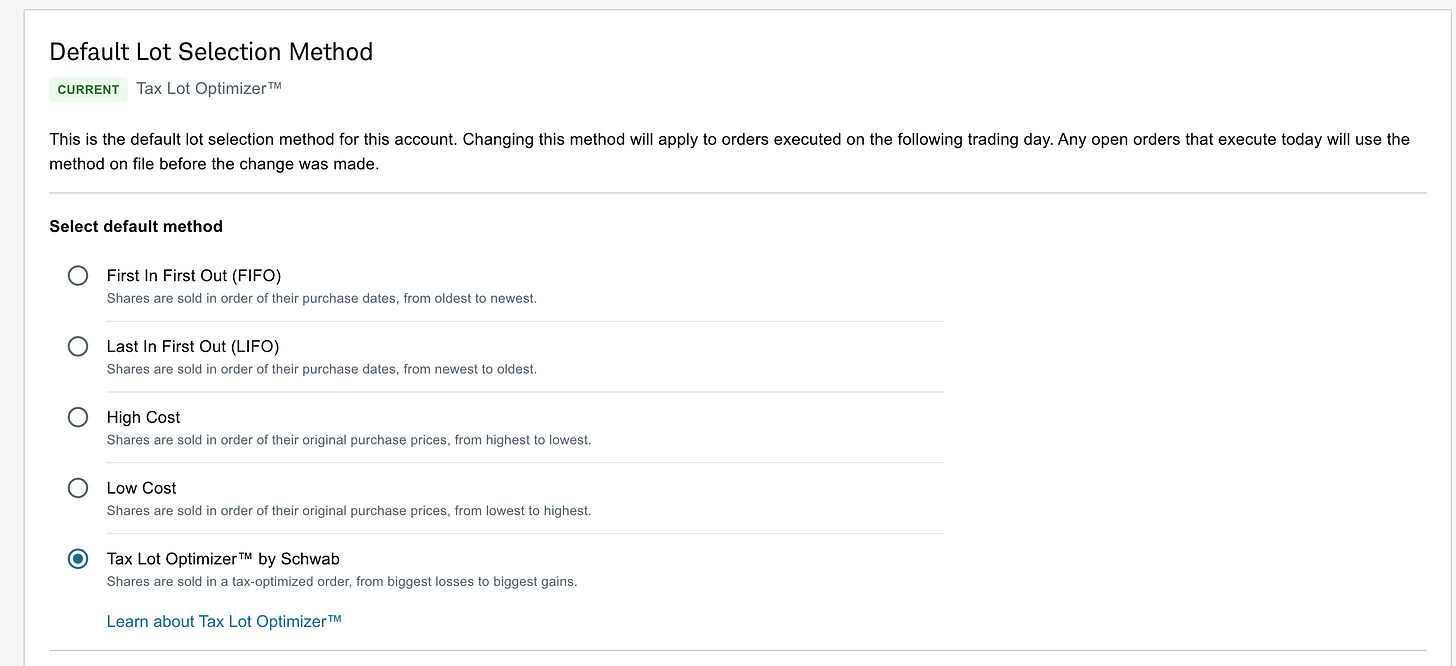

With Schwab, once you’re logged in, select “Cost Basis Methods” under your Profile in the top right corner.

From there, you will see your current selection method. You can then adjust this to your heart’s delight (and your accountant’s relief).

Conclusion

Understanding cost basis and disposal methods isn’t exactly cocktail party conversation, but it can save you real money. Review your settings, talk to a pro, and don’t forget to check your disposal method before selling anything. Otherwise, you might accidentally send the IRS a very generous holiday gift.

That's it for this week! As always, no financial decisions should be made solely on this newsletter, which is for informational and entertainment purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for advice from a professional financial advisor or qualified expert. If you haven’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter below and never miss an update: